Fons et origo

My winning blog topic this evening is a hole in the ground.

But not just any old hole in the ground. This hole is smack in the middle of my college and, as the more perceptive among you will already have spotted, a well.

We had no idea it was there. The quad in which it was found, Chapel Quad a.k.a. the Deer Park (our ironic competition with Magdalen College’s Deer Park, which contains real deer), is being re-landscaped, but the well doesn’t appear on any plans, and gets no mention in our records, so it was quite unexpected. There’s no sign of it either on Loggan’s engraving of the college from 1675 (the red line marks the spot), and the college records of works thereafter are pretty comprehensive. That said, there is some writing within the well, the letters H G(?) and 18 (the well is about 5m. deep, so that might be its height/depth in feet, but what do I know), so someone’s been down it at some point. (The lead pipe in the picture is a later addition, presumably dating to whenever it was that the well was capped, and designed to provide pumped water from it.)

So the well is older than the late seventeenth century, and we also have a terminus post quem: in the fill of the well’s construction trench archaeologists from Oxford Archaeology (source also of the photo at the head of this post) found a single sherd of pottery datable to the fifteenth/sixteenth century.

That places us at a very interesting time. Brasenose College was founded in 1508-12, on the cusp of the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII. But the well is close to, and likely closely associated with, a building now known as the Medieval Kitchen (just behind it on Loggan’s engraving), which stands at an odd angle to the other college buildings and is presumed to be a survival from before the foundation of the College. Assuming that the well and the Medieval Kitchen are coordinated, it seems likely that the well predates the College, too.

Before Brasenose College was founded, this part of Oxford was a jumble of smaller academic institutions, the halls which preceded the establishment of the larger, endowed colleges. Then, as now, the vicinity of St Mary’s church, the University Church, was the heart of the University: in 1408-9 as many as thirty-two halls lined (the aptly named) School St. This now survives as the west side of Radcliffe Sq, mainly taken up by one side of Brasenose College. It once extended to the northern wall of the city, until blocked by an extension to the Bodleian Library.

These academic halls were places where small numbers of students would live and receive lectures: they typically had the form of medieval town houses, a ground-to-roof hall with rooms attached, the hall for eating and lecturing, the rooms for study and sleep. On the site now occupied by Brasenose, as the map below (from Volume 1 of the Quatercentenary Monographs produced by the College in 1909) indicates, there were at least ten academic halls, Broadgates, Haberdashers’, Little St. Edmund, St. Mary’s Entry, Salesurry, Brasenose, Little University, Ivy, St Thomas’ and Shield. Brasenose Hall, in existence since the thirteenth century, had its entrance where the current College entrance is, and is its most significant precursor. The first Principal of “The King’s Hall and College of Brasenose” (to give us our full name), Matthew Smyth, had been Principal of Brasenose Hall, and of course the new foundation adopted its peculiar name.

Over the centuries Brasenose College expanded to fill the space occupied by these halls, but the bit of college we’re concerned with, the Deer Park, only really joined the College when laid out as a second quad in the seventeenth century, just a few years before Loggan’s image. On this map of the site of Brasenose in 1500, just before the college was founded, it is marked VII, and this was the location of the academic hall known as St Mary’s Entry (I here acknowledge my debt to my polymathic colleague Jonathan Jones).

St Mary’s Entry, Introitus Sanctae Mariae in Vico Scholarum in contemporary records, seems to have been a comparatively recent establishment, dating to the second half of the fifteenth century. It and Salesurry Hall (VIII) were granted in perpetuity to one of the founders of Brasenose, Sir Richard Sutton, by Oriel College, its owner, on February 20, 1509/10 (at a rent of 13s. 4d). That “Medieval Kitchen”, meanwhile, is a mystery: “It has a fine open-timber roof, apparently of an earlier date than anything else we have, and has every appearance of being an older building, incorporated into the College,” in the words of Quatercentenary Monograph. My entirely uninformed guess is that the Medieval Kitchen and the hall of St Mary’s Entry are one and the same, and that it and its associated well belong to that time just before the foundation of the College by Royal Charter, at which point most, but evidently not quite all, of what preceded it was flattened and replaced.

“Medieval Kitchen” (St Mary’s Entry?) interior

I like wandering around this city and imagining the very different appearance it had in the past. It’s a paradoxical thing, since Oxford’s cityscape is already so very old. But Oxford is also a place where building has never stopped, and the centre of the University, Radcliffe Sq, is especially transformed from its appearance 500 years ago. Our “Medieval Kitchen” may well be a fragment of that earlier, more ramshackle University of Oxford. I’m also fascinated by the hidden history of its buildings: I speculated on the history of another part of Brasenose College here, and also imagined the suburb of Oxford where I live when it was still open fields, hosting an encounter between James I and dignitaries from the City and University in 1605.

But there’s nothing more evocative than a well for representing the distant, forgotten past, reaching deep down into the ground beneath us.

P.S. For another blog on the subject, and this one written by an archaeologist who knows what she’s talking about, Francesca Anthony, see here.

“Medieval Kitchen” exterior (with the well beneath the metal fencing to the right)

Map of the College shortly post-foundation, suggesting that the “Medieval Kitchen” is an element retained from St Mary’s Entry.

When the spade you call a spade’s no spade

My least snappy title by a distance. Apologies, and apologies also for a blog inspired by a pun so obscure that I’ve seen it attributed to two Oxford Classicists separately. Actually it was really inspired by Claire Webster, to whom thanks.

“To call a spado a spado” is a joke that Claire heard Tom Braun, a Classicist at Merton College, make, but I can claim an earlier outing. A former student of my college, Brasenose, recalls attending lectures in the 1950’s on the Roman satirist Juvenal, delivered by J.G. Griffith of Jesus College. Juvenal does not pull his punches, and Griffith, clearly a don of the old school, “felt inhibited” discussing his poetry “when lady students were present.” When the last of the women undergraduates eventually left the group, he remarked with relief, “At last: now I can call a spado a spado.”

Not a very edifying scene to contemplate, and I’ve got a feeling this joke has been told for as long as Juvenal has been taught through the medium of English. Allow me to explain it. A spado in Latin is a eunuch, and though Juvenal in actual fact used the term sparingly (only three times in total), eunuchs were very much the kind of affront to Roman manhood that Juvenal’s spectacularly jaundiced style of satire specialised in attacking. In Satire XIV, for example, he lays into the spado Posides, a freedman of the emperor Claudius, for his extravagant building projects (see here for what might have been one of his villas on the Amalfi Coast), but it’s probably more relevant that when Juvenal launches his satirical project in his scene-setting first poem, explaining that he’s been driven to abusive poetry by the moral corruption he sees all around him in the city of Rome, it is with a “soft spado” taking a wife (cum tener uxorem ducat spado) that he begins (1.22).

The expression “to call a spade a spade” of course means to speak frankly and directly, to tell it like it is. A spade’s spadiness is the perfect analogy because it’s an utterly unexotic piece of equipment, with entirely practical and unglamorous uses. In fact humour can be got from the perceived distance between spades and specialness (“to call a spade a geomorphological modification implement”) or from intensifying the spade’s mundane associations (“to call a spade a bloody shovel”). Calling a spade a spade is a quality or disquality we could easily associate with Juvenal, and J.G. Griffith could apply it to the less roundabout style of discussing Juvenal’s satire he felt able to adopt once all the women had left the room. Hence “to call a spado a spado“.

Ho ho.

Now, I’m not going to devote an entire blog, composed in the precious hours I’ve snatched from my new life as an administrative drone, to explaining a donnish pun. Luckily the original expression “to call a spade a spade” has its own rather interesting history.

Like a lot of colloquial expressions that we assume are just traditional, or maybe biblical, this is anything but. We owe it to the great humanist Erasmus, and the collection of aphorisms, the Adages, which he first published in 1500 but added to for the rest of his life, so that in its final form, in 1536, the Adages reached a total of 4,151 entries, a Herculean achievement as he himself described it. These proverbs were then translated from Erasmus’ Latin into the vernacular languages of Europe, and the result is that our everyday language is peppered with Erasmian maxims: if you ever talk about “a necessary evil”, “rare bird”, “squeezing water from a stone”, “looking a gift horse in the mouth”, “putting the cart before the horse”, you owe that turn of phrase, and heaps of others, to Erasmus.

These proverbs weren’t Erasmus’ own invention. He found most of them in the Greek and Roman literature that, as a Renaissance humanist, he saw as the key to building a civilized society. It helped that he achieved an encyclopedic knowledge of that literature. There really wasn’t much that Erasmus hadn’t read at some time or another. I once traced the common turn of phrase “to lose a battle, but not the war” back to Erasmus’ Adages, but he’d found it in the late-antique dictionary of Nonius Marcellus, which he read and exploited for the penultimate 1533 edition of the Adages. I confess it tickles me that people, in the normal course of conversation, unwittingly repeat the words of classical writers: “a necessary evil” comes from the Greek geographer Strabo, “in the same boat” from a letter of Cicero, “one swallow does not make a summer” from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, “a friend in need is a friend indeed” (a jingle in Latin, too: amicus certus in re incerta cernitur) from a tragedy of Ennius via Cicero, “to lose a battle but not the war” from Juvenal’s great predecessor in Roman satire, Lucilius (for whom Nonius’ De compendiosa doctrina is an important source). It tickles me especially that the expression “to call a spade a spade”, which is all about using simple language, is actually the result of the most learned man of his day’s unparalleled familiarity with the literature of classical antiquity.

We’re all Classicists really, it’s just that some of us don’t know it yet.

“To call a spade a spade” is just one of these 4,151 aphorisms, no. 1205, in fact. But it has an especially interesting history. Erasmus introduced it, in the 1515 edition, as Ficus ficus, ligonem ligonem vocat, “He calls figs figs, and a hoe a hoe.” “It is applied,” he explains, “to the man who explains something as it is, with simple, rustic truthfulness, and does not wrap it up in complex or elaborate expression.” He traces his Latin version of the saying to a Greek original, ta suka suka, ten skaphen skaphen legon (τὰ σῦκα σῦκα, τὴν σκάφην σκάφην λέγων), a line of verse which he attributes to Aristophanes, the most famous writer of Attic Comedy, apparently on the basis of reading John Tzetzes, a twelfth-century Byzantine scholar. The saying itself he found in one of his favourite ancient writers, the Greek satirist Lucian: in Jupiter Rants (Zeus Tragoidos 32), Heracles excuses himself as a “country bumpkin” who, “in the words of the comic poet” calls “the skaphe skaphe” (for reasons that will become clearer, I’ll hold off translating skaphe for the moment); while in How To Write History (41) Lucian lists the qualities of a good historian, “fearless, incorruptible, independent, a lover of frankness and truth, prepared, as the comic poet says, to call ‘figs figs, and the skaphe skaphe‘.” The full expression in How To Write History, figs and all, probably comes from another comic poet (though in a very different style of Comedy), Menander (fr. 717 Koerte). But the source of the version in Jupiter Rants (Aristophanes fr. 927 Kassel-Austin) may indeed be Aristophanes, depending how much faith we place in Tzetzes (traditionally, not awfully much).

This Roman hoe, from the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, is a Roman hoe.

For its impact on our everyday speech, Erasmus’ Adages is one of the most influential books ever written. In relation to no. 1205, the English versions of the Adages that rapidly appeared, for example by Richard Taverner and Nicholas Udall, rendered Erasmus’ ligo as “spade”–hence the aphorism we still use today. But there’s one odd thing we haven’t mentioned about Erasmus’ 1,205th adage: it’s all wrong. The Greek word that Erasmus translated as ligo, “hoe,” and Udall as “spade”, skaphe (σκάφη), means no such thing. A skaphe is not a tool for excavating but something excavated, a dug-out canoe or, in this case, probably a kneading trough or dough bin. Now, “to call a kneading trough a kneading trough” references an appropriately mundane item of kitchen equipment, it is true, but it lacks the snappiness of “calling a spade a spade”. “Spade”, “hoe” or “mattock” σκάφη simply does not mean, and it reminds us that Erasmus’ learning of Greek was always a work in progress, but his blooper was serendipitous if, as I suspect, it ensured the popularity and endurance of the English expression.

There we have it, anyway, the history of a turn of phrase which we may not have imagined had much of a history. On the contrary, when you bluntly call a spade a spade, you are echoing the language of Athenian dramatists from 2,500 years ago, with a twist added quite unwittingly by the leading light of the northern Renaissance.

Notes on a note

In the archives of Rhodes House, the home of the Rhodes Trust in Oxford, I came across a nondescript handwritten note.

It was in the student file of Justus Carl von Ruperti, a German World War II fatality (and Rhodes Scholar) who has an arrestingly unexpected memorial in Brasenose College chapel. I blogged about him a couple of months ago, but hadn’t at that stage seen his record at Rhodes House.

When I did, I found what I’d found in his Brasenose record, details of his admission, the wonderfully brief comments that counted as termly reports in the 1930s, and nothing very illuminating until the note that someone, sometime had thought to slip into his file.

It is written by “R.” to “M.P.”, and carries no indication of a year, but it describes a visit by Juscar von Ruperti’s mother Irma to Rhodes House:

M.P

The mother of J. C. von Ruperti called 9 September. She was sorry that you were on holiday, as she would have liked to meet someone here who’d known him. She went round R. Hse, saw War Memorial, and departed with a grey booklet, which was the best I could offer after you.

R.

At the bottom is scribbled an answer from “M.P.”: “I can’t remember him as well as some of the nice German Rhodes R[hodes] S[cholar]s.”

I can never resist inadequately dated, initialled notes, and with the brilliant help of Melissa Downing, the archivist at Rhodes House, I now know that “M.P.” was Marjory Payne. Whenever it was that Irma von Ruperti visited, she wanted to meet someone who’d been there in 1933-35, when Juscar was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. Marjory had been Assistant Secretary at Rhodes House from 1928 to 1936, and then the Warden’s Secretary from 1936 to 1957.

Actually, that also helps to date the note. If there was no one at Rhodes House who’d known Juscar when Irma visited, we must be after the retirement of Sir Carleton Allen, Warden 1931-52. Marjory Payne retired in 1957, and September 9 in 1956 was a Sunday. We must be between 1952 and 1955, or maybe in 1957, and since the memorial in Brasenose chapel was installed in 1954, my hunch is that Irma was in Oxford to see it, possibly even to attend its inauguration, if there ever was an inauguration. There is precious little reference to Von Ruperti’s plaque in the Brasenose record.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in the last two years researching and writing about Brasenose war dead. The most poignant thing, I suppose predictably, is also the least visible thing, the impact of war on the surviving family: what will always stay with me about Bob Brandt, for example, are the In Memoriam notices his mother placed in The Times every year without fail until shortly before her death.

Here again in the Rhodes House archives I was contemplating a grieving mother, and I find impossibly moving this record of Irma von Ruperti’s unrealised hope of speaking to someone who remembered her son. She had lost both her sons in the war, and had been a widow since 1945; she herself lived until 1980. She wasn’t just the mother of a war casualty, of course, but the mother of a man who had died fighting on the other side. I do wonder what it was like for such a person to visit Britain in the 1950s.

“R.” (whom I also hope to identify in time)** tells Marjory that s/he sent Irma off with a “grey booklet”. This was Cecil Rhodes and Rhodes House, a guidebook that explained the development of the Rhodes Trust as well as describing Rhodes House. In that booklet, if Irma read it, she would have learned that ‘the German Scholarships were created because “the German Emperor [Kaiser Wilhelm II] had made instruction in English compulsory in German schools”, and in the hope “that an understanding between the three strongest Powers [Britain, Germany and the United States] will render war impossible and educational relations make the strongest tie’,”‘ both quotations from a codicil to Cecil Rhodes’ sixth and final will in 1901, by which he established Rhodes Scholarships for Germany.

If Irma did see the Brasenose memorial on this visit, she will have seen her son’s name both in Brasenose and at Rhodes House: the war memorial there, containing the names of all Rhodes Scholars regardless of nationality killed in the First and Second World Wars, is inscribed below the dome of the Rotunda at the entrance from South Parks Road. (There’s a virtual tour of Rhodes House here, with the Rotunda at the top.)

**Thanks again to Melissa Downing, who has now discovered that Rosalind Wellstood worked as Assistant Secretary at Rhodes House from 1951 to 1953, and is probably the author of the note. It follows that Irma von Ruperti made her visit to Rhodes House on Wednesday 9th September, 1953. Just three weeks previously she will have marked the tenth anniversary of her son’s death in Russia.

On a foot that walked

(Image from Bernard (1969), 339)

A short blog, and a pendant, really, to my wild speculations in the last one.

I’ve been reading this excellent little book on Ai Khanum, the “Greek city” on the Oxus river in NE Afghanistan that was excavated by French archaeologists between 1964 and 1978. An image of the amazing find at the top of this blog, the perfectly lifelike foot of a god (on which more later), left me wondering, given all the perils that have beset Afghan antiquities in the last few decades, what had happened to it. Eventually I realised that I already knew the answer.

The foot in question was discovered in 1968 during the excavation of one of the major religious building discovered at Ai Khanum, the “Temple à redans” or “Temple with indented niches”. It is the fore portion of a left foot, sandalled. The French excavator Paul Bernard, in his report of the season’s excavations (CRAI 113 [1969], 313-55), has a marvellous few pages (338-41) extrapolating from this 27cm-long artefact to the statue it originally came from.

It was the cult statue of the temple, the god to whom the temple was dedicated, and had been positioned at the back of the cella of the shrine, the focus of a worshipper’s attention. It was of colossal proportions, two or three times life size, and the fact that only extremities of the statue were found, coupled with the shape of the back of the foot fragment, led Bernard to conclude that it was an acrolith, its head, hands and feet carved from marble and the rest of its body in unbaked clay moulded over a wooden armature, a technique typical of Greek sculpture at the time of the construction of the temple at Ai Khanum, about 250BC. Bernard was convinced that the foot could only have been carved by a Greek sculptor.

The god’s foot was sandalled, and again it is a typically Greek form of sandal that he was wearing. The straps of the sandal are decorated with palmettes and roses, and also with a motif that may point to the identity of the god represented, two winged thunderbolts. On this basis Bernard proposed that the god was Zeus, and furthermore that the dimensions of the cella in which he was located suggested a seated figure, “a Zeus enthroned in majesty as he is represented in Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek coinage, with his left arm drawn back holding the sceptre and his right hand advanced carrying the eagle of a figure of Victory.” If he was Zeus, though, he was most likely a Zeus assimilated to an eastern divinity: the temple in which this Greek statue sat or stood was distinctly un-Greek in architectural form and hence, one assumes, liturgical practice. Maybe he was both Zeus and Ahura Mazda or Mithra, or maybe (my personal favourite suggestion) the river god Oxus himself.

This fragment of Zeus enthroned on the banks of the Oxus in time took its place in the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul, in its heyday one of the great museums of the world, but one that (like the country it represents) has suffered much misfortune since. The damage wrought by the Taliban with their pickaxes in the Museum is familiar, but the foot was no longer there to be smashed when the Taliban came in 2001. Between 1992 and 1994 Kabul fell into chaos as a bewildering range of armed groups fought for control of the capital. In the midst of intense civil conflict the Museum suffered structural damage, and there was extensive looting, a lot of it pretty obviously to order. When in 1995 an inventory was taken of the Museum’s holdings, the foot was gone, along with many treasures from this remarkable institution, most notably the contents of its superb pre-war coin room.

From the mid-nineties until 2001 the trail went cold, but in April 2001 news reports surfaced announcing the presence of Zeus’ foot in Japan. On April 17, 2001 the Japan Times reported that “the marble foot of Zeus, dating back to the third century B.C.,” would be put on display at the Ancient Orient Museum in Tokyo. The report claimed that the artefact, illegally removed from Afghanistan and put up for sale on the international art market, was bought by “an anonymous benefactor in Tokyo”, “on condition that it be returned to Afghanistan when peace is restored there.”

This is all a little murky. April 2001 was a convenient moment to come clean about Afghan antiquities bought on the art market. In February Taliban had entered the Museum in Kabul and smashed any statues they considered idolatrous; in March the Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed. It was a good time for Afghan antiquities not to be in Afghanistan, and for art dealers to be heroes.

That may be excessively cynical. Earlier this year, at any rate, concrete commitments were made to return the foot to the Afghans. (I saw these reports in the summer, but didn’t put two and two [or should that be toe and toe?] together.) The context is the imminent arrival in Japan, from the start of 2016, of the touring exhibition of material from the National Museum in Kabul, “Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul”, since 2008 under the aegis of National Geographic. This exhibition has been staged in Europe and the US, Canada and Australia; it was at the British Museum in 2011. In connection with the exhibition’s arrival in Japan, it was announced that 102 Afghan artefacts from the National Museum collected by the Japan Committee for the Protection of Displaced Cultural Properties would be added to the touring exhibition, including “a fragment of the Left Foot of Zeus (3rd Century BC)”.

The Japan Committee for the Protection of Displaced Cultural Properties is certainly kosher. It was established in 2001 by a Japanese artist and academic called Ikuo Hirayama, a survivor of Hiroshima who had visited Afghanistan in the 60s and 70s, drawn most of all to Bamiyan, a place of course associated with Japan’s national religion of Buddhism, but specifically with the figure of the Chinese monk and traveller Xuanzang, a revered figure who provided the very earliest description of Bamiyan, then a flourishing Buddhist kingdom, when he passed through the Hindu Kush on his way to India in AD630. It was the Silk Road, the scene of Xuanzang’s epic travels, that really fired Hirayama’s imagination.

Hirayama died in 2009, but spoke movingly and forcefully about his experience of Bamiyan as a Buddhist on his first visit in 1968, and what should and should not happen to the site after the statues’ destruction by the Taliban. One of his images of Bamiyan can be seen here, and more of his art here. But if it was Afghanistan’s Buddhist past that drew Hirayama to Afghanistan, he became committed to protecting the country’s cultural heritage as a whole, and this mass repatriation of material is very much his personal legacy. (For another example of this remarkable man’s philanthropy, see this blog on the British Museum’s Hirayama Conservation Studio.) It’s a qualified positive, all the same: a return of artefacts so long after 2001, and at a time when Afghanistan appears a lot less stable than, say, in 2008. One senses there was some tough negotiation in the background. Also, though, the repatriation is not so much to Afghanistan as to a touring display of Afghan treasures that are never actually on display in Afghanistan. That will be the moment, when Afghanistan is peaceful enough, and has a National Museum secure enough, to host in Kabul itself the Begram hoard, the Tillya Tepe gold, and the amazing finds from Ai Khanum, including Clearchus’ inscription and Zeus’ left foot.

I’m particularly fond of globetrotting Greek gods: there is another one here, Athena. And another one, Hercules, here. But the globetrotting foot of a Greek god seems particularly apt, carved by a Greek in Afghanistan, 3,000 miles as the crow flies from Greece, spirited away to Japan via the Peshawar bazaar, now part of a perpetually travelling exhibition. I hope one day I set eyes on it, when that exhibition passes by the UK again, or (who knows?) maybe even in Kabul.

An archaeological whodunnit

A more misleading title to a blog you will never see. There’s no murder here, no crime at all. No tension or thrill for that matter. There is a slight mystery, maybe even a touch of deceit, but I’d be kidding you if I pretended this was anything other than the most self-indulgent blog I’ve ever written. Not least because it’s about Afghanistan, a place I keep trying not to write about. It’s just too fascinating.

In 2008 I got to visit Ai Khanum, an archaeological site on the northern border of Afghanistan. It is not an easy place to get to, and it was one of the highlights of my life, an unforgettable 40th birthday present from Alan MacDonald, at the time based in Afghanistan with MACCA, the Mine Action Coordination Centre of Afghanistan. Here I am at the site, the River Oxus and Tajikistan behind me, feeling short alongside Alan and two Afghan MACCA officials, Mohamed Shafiq and Sayed Aga.

Even without the archaeology Ai Khanum is a stunning location, set in the angle created by the confluence of the Amu Darya (Oxus) and the Kokcha rivers. The site was dug by French archaeologists in the sixties and seventies, and they found some quite spectacular things. It was a city established by Alexander or one of his successors 3,000 miles away from Greece, but equipped with characteristically Greek things like a theatre, gymnasium and stocks of olive oil, even Greek texts: some of the texts themselves, parts of a philosophical dialogue, weren’t actually found, but the imprint of their ink had been left on the earth.

Much of what was brought to light at Ai Khanum illustrated the nostalgia of the Greek colonists for their homeland, and there was plenty of evidence also of the compromises they were obliged to make with their new and radically different environment. The city traded in the most famous product of its hinterland in Badakhshan, lapis lazuli, and some of the city’s architecture, and by implication some of its religion, politics and social life, was more middle-eastern than Greek. But however one cuts it, Ai Khanum represented a fascinating encounter between Greek and non-Greek culture.

My very favourite artefact, probably the main reason I wanted to see the place, was a visually unappealing block of stone inscribed with Greek, some lines on the ideal life (originally inscribed at the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, in Greece) and a poem explaining how a man called Clearchus had travelled all the way from Delphi to Ai Khanum and set up the monument when he arrived. There’s more on Ai Khanum and Clearchus’ inscription here; a 3D video tour of the reconstructed city here; and a while back I tried to explain the significance of Clearchus’ journey here. The Delphic wisdom was as follows:

Παῖς ὢν κόσµιος γίνου

ἡβῶν ἐγκρατής

µέσος δίκαιος

πρεσβύτης εὔβουλος

τελευτῶν ἄλυποςAs a child, be orderly,

As a youth, be self-controlled,

As an adult, be just,

As an old man, be of good counsel,

When dying, feel no sorrow.

So, an exciting archaeological site for any Classicist, but especially one with a thing about Afghanistan like me. But that’s not quite what I’m concerned with in this blog. Ai Khanum was excavated from 1964-78 by the archaeologists of DAFA, the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan. Something that has intrigued me for a long time is the official account of how the site was originally discovered in the sixties. In 1961, the story goes, the king of Afghanistan, Zahir Shah, was shown some impressive archaeological fragments (one of them a large Corinthian capital) during a hunting expedition. He then summoned the Director of DAFA, Daniel Schlumberger, to an audience, and requested that the archaeologist visit the site to assess what he had seen. It’s a great story, the King inspiring the archaeological investigation of Afghan history, and I suppose that’s exactly what makes me suspicious.

Ai Khanum had certainly been “discovered”, in some sense, earlier than 1961. In 1836-8 Captain John Wood, on the skirts of a mission to Kabul led by the greatest of the Great Game operators Alexander Burnes, travelled through what is now north-eastern Afghanistan, then the territories of the terrifying ruler of Qunduz, Murad Beg, tracking the course of the river Oxus to its source, or at least one of its sources. Later, on 18 March 1838, during a journey out from Qunduz with Dr Perceval Lord (whose medical treatment of Murad Beg’s brother had been what gained Wood access in the first place), he visited “I-khanam” where, he was informed by locals, “an ancient city called Barbarrah” had stood. A century later in 1926, in the very early days of DAFA (which was established in 1922 by agreement between Amanullah, King of Afghanistan, and the French archaeologist Alfred Foucher), Jules Barthoux set off on a tour of northern Afghanistan in search of promising sites for investigation. One of them was “Aï Khanem”, identified in Barthoux’s notes, in Foucher’s report of his tour to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in Paris, and even on a map of Afghanistan in an article in the French national newspaper Le Temps on 6 July 1930, as a place of archaeological interest.

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

Now, a lot happened between 1926 and 1961, and Barthoux had parted company from DAFA on poor terms. There’s also a difference between a general sense that there’s something very old to be found, and the very specific pieces of Greek archaeological material to which Zahir Shah alerted Schlumberger. So I’m prepared to believe that Barthoux’s information about Ai Khanum had been forgotten by the sixties, or at least that it hadn’t struck anybody as of urgent importance. The same could be said for John Wood’s account in A Personal Account of a Journey to the Source of the Oxus, although Paul Bernard, who directed the excavations at Ai Khanum, did later base some speculative but very interesting arguments about its early history on Wood’s account.

Let’s assume, at any rate, that it took Zahir Shah’s intervention to alert Daniel Schlumberger and Paul Bernard to the archaeological potential of Ai Khanum. I’m not so sure that it was such a revelation for the King of Afghanistan himself.

In 1923 Burhan al-Din Kushkaki published Rahnuma-ye Qataghan wa Badakhshan, an abridged version of a report by Mohamed Nadir Khan of a tour of north-eastern Afghanistan in 1921-22. Nadir Khan was at the time Minister of Defence, and he and three other ministers had been dispatched by the reforming King Amanullah, shortly after his accession in 1919, to report on various parts of the country. In effect, the Rahnuma was part of Amanullah’s Domesday Book. One of the places visited by Nadir Khan was called ای خانم, Ai Khanum, “which in ancient times had been a city”. Like all previous visitors to the site, Nadir Khan noted the traces of buildings still visible.

Nadir Khan later became king himself, after Amanullah’s overthrow in the events I described here. But probably the most relevant thing about Nadir Khan is that he was the father of Zahir Shah, the king who supposedly discovered Ai Khanum on that hunting expedition in 1961. The Rahnuma was translated into Russian in 1926, for obvious reasons given the proximity of the Soviet Union. It wasn’t translated into French until 1979. But while the archaeologists of DAFA were very likely unaware of it, I doubt that Zahir Shah was.

What I wonder is whether Zahir Shah had reasons over and above an interest in archaeology to push DAFA towards Ai Khanum at this time. Something to be understood is that Zahir, though king, was not the real power in Afghanistan at the time. As Tamim Ansary explains in Games without Rules, his wonderfully readable history of modern Afghanistan, since 1929 Afghanistan had been ruled less by individuals than by a family, or “the Family”, as Ansary calls it, the collectivity of the male members of the Musahiban clan. In 1961 real power resided with Daoud, Zahir’s cousin, officially the Prime Minister. A couple of years later, in 1963, Zahir Shah managed to sideline Daoud, assume power himself, and enact sweeping democratic reforms. In 1973 Daoud took power back from Zahir, but in the process unleashed the radical left-wing forces which would see Daoud ousted and killed in 1978. Up until 1978, however, change of regime in Afghanistan was actually just a reshuffling of the Musahiban cards, the result of internal, and necessarily largely invisible, politicking within the Family.

I think we can see hints of this politicking in the events surrounding Ai Khanum in 1961. Zahir Shah had encouraged Schlumberger to visit Ai Khanum, but Schlumberger had to return to his university in France for a spell and deputed another French archaeologist to go in his place, Marc Le Berre. The King gave Le Berre authorisation to travel to Ai Khanum, but the local governor refused him access. Eventually Schlumberger visited the site in December 1962, and was convinced of its importance. In a report Schlumberger commented on the fundamental importance of securing the approval of the Prime Minister, Daoud, for their proposed excavations. And yet Zahir Shah by his initiative, aided by the spectacular character of the archaeological site he had brought to DAFA’s attention, got his way.

I don’t think it’s too hard to see this as the King using the foreign archaeological mission to assert his own authority. What made Ai Khanum especially sensitive was its location right on the border with the Soviet Union. Generally the French archaeologists in Afghanistan avoided going near the borders; as it was, a token number of Soviet archaeologists were included in the team when excavations got fully under way in 1965. But an exciting, internationally significant archaeological excavation on the Soviet border initiated by the King had its own symbolism. When Zahir Shah ousted Daoud shortly after, the new policies involved, among other things, a turn away from Daoud’s reliance on the Soviets, an opening up to the outside world, an emphasis on cultural openness and education. Internally and externally, it seems to me, the processes that Zahir Shah kicked off by his audience with Daniel Schlumberger answered to those aims rather precisely.

Well, maybe, maybe not. But I’d like to believe there was more to Zahir Shah’s hunting trip than meets the eye.

A few things last week set me thinking again about this question. The main one was a Twitter conversation with Mary Munnik in which it came home to me, for far from the first time, how utterly opaque Afghan politics are to me, ancient, medieval and modern. That should be borne in mind when assessing my musings above: I really and honestly don’t have a clue, but I can’t help but find it all thoroughly fascinating.

I’ve read or re-read some interesting stuff on DAFA, Zahir Shah, and Ai Khanum in the last few days:

Tamim Ansary, Games without Rules (2012);

Paul Bernard, ‘Aï Khanoum “La Barbare”‘ & ‘La découverte du site grec et de la plaine d’Aï Khanoum par John Wood’, in Paul Bernard & Henri-Paul Francfort, Études de géographie historique sur la plaine d’Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan) (1978), 17-23 and 33-8;

Rachel Mairs, The Hellenistic Far East: Archaeology, Language, and Identity in Greek Central Asia (2014);

Françoise Olivier-Utard, Politique et Histoire: Histoire de la Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (1922-1982) (1997);

Marguerite Reut, Qataghan et Badakhshan, par Mawlawi Borhan al-Din Koshkaki Khan (1979);

Zamariallai Tarzi, ‘Jules Barthoux : le découvreur oublié d’Aï Khanoum’, CRAI 140 (1996), 595-611.

For his Country

The chapel in Brasenose College, Oxford, like any college chapel, is festooned with memorials: principals, senior fellows like Walter Pater, and on the southern wall of the ante-chapel, a handful of former students. The first few are Indian Civil Service, and the very first one attempts to capture life and death in a modern colonial bureaucracy in Latin: the ICS becomes CIVILE MUNUS APUD INDOS. Thereafter they stick to English, no doubt wisely, but one of them is for my money the most remarkable, thought-provoking epitaph in the whole building, possibly in Oxford. It’s a plain sheet of brass, as restrained in its language as its form:

What the viewer realises with a start, of course, is that the country for which Justus Carl von Ruperti fought and died was not this country but Germany. The presence of a memorial to an enemy combatant in an Oxford chapel is arresting enough; the fact that it was first proposed in 1950, as it turns out, is something I find stunning. All in all, even though Richard Davenport-Hines gets the details a bit wrong (Ruperti’s memorial is separate from the main World War II memorial), he’s right that it “is heart-stopping to anyone who sees it.”

What follows are the fruits of some research on Ruperti’s plaque, all driven by my fascination for a memorial to a German soldier erected within a very few years of the War. I’ve found some information in the records of Governing Body meetings in Brasenose, although they record the very minimum, and Justus Carl’s nephew, Lippold von Klencke, has been incredibly generous with information from family documents. Ruperti’s student file, though again extremely spare by today’s standards, had some interesting details. But I’m sure there’s more to know, so please don’t hold back if you can help. For example, I find not a hint of controversy surrounding the decision to commemorate Ruperti, and that surprises me. There are a few memorials to German war dead around Oxford (Oxford had had many German students), but they’re not a subject that’s much talked or written about. At New College there’s a separate memorial for World War I, but none for World War II. At Merton College two names of German dead were added to the World War I memorial in 1994. At Balliol College I know that the inclusion of five German names from World War II, only one of them a combatant, provoked objections from old members when it was proposed in 1947. When Konrad Adenauer, the German Chancellor, toured Oxford in 1951, visiting the memorial in Balliol that carried his nephew’s name, there were protests at Oriel College which forced him to change his itinerary. At Brasenose, there is very little information at all.

Justus Carl von Ruperti, always Juscar to friends and family, was a Prussian aristocrat, his father Max von Ruperti a high administrator, Regierungspräsident of Allenstein, one of the three administrative regions of East Prussia: the regional capital, Allenstein, is now the Polish city of Olsztyn. Within Ruperti senior’s jurisdiction, to the south of the city of Allenstein, stood the Tannenberg Memorial, which commemorated an overwhelming German victory over Russia in 1914 by evocation of the medieval Teutonic Knights, folkloric champions of Christianity and defenders of the eastern frontiers of Germany. Tannenberg was a potent expression of German national identity.

I mention the Memorial because it gives a sense of the times, and because in 1932 it was the catalyst for conflict between Max von Ruperti and the NSDAP, the Nazi Party. Hitler, characteristically, saw Tannenberg as an opportunity to promote his own political agenda, but Ruperti refused to allow a Nazi rally to be held at the site, on the grounds that it contravened the essentially non-partisan nature of the Memorial. When Hitler came to power after the elections in March 1933, Ruperti was summarily sacked as a consequence.

What I’ve been trying to do in the last few weeks is understand the motivations of Juscar von Ruperti, who after all died fighting in Hitler’s war, and understand the thinking of the Brasenose fellows who decided to commemorate him. One thing that helped me understand was one of the first things I discovered, which was that the moving force behind Juscar’s memorial was Barry Nicholas, a Law Fellow and later the Principal of Brasenose, who had himself served in World War II. I knew Nicholas myself very much in passing, but found myself studying his life in some detail a few years back when I had the nerve-wracking job of composing a Latin memorial for him after he died in 2002. It now hangs on the wall just a few feet from Juscar’s. What I discovered about Nicholas is what Harry Judge describes in this obituary: he was a remarkable man, principled, humane and profoundly wise, someone I would trust implicitly to be right about something like this.

But back to Tannenberg. The memorial is now totally obliterated. This blog tells the story of the aftermath of its abandonment in the face of the Soviet advance in 1945. But while it existed it was an unapologetically nationalistic monument, and when we, in 2015, look at images of its severe, völkisch architecture, we struggle to dissociate what we see from expressions of Nazi ideology. But the Memorial was conceived and built well before the Nazis took power, even though later appropriated and redesigned by them, and Max von Ruperti combined patriotism with courageous and principled opposition to the NSDAP.

In 1931 the Canadian Kathleen Coburn stayed with the von Ruperti family in Allenstein. She found them open-minded, opposed to militarism, and motivated by a strong social conscience. Coburn accompanied Frau von Ruperti, Juscar’s mother, to see the welfare initiatives that she patronised in Allenstein, impressive efforts to counter the impact of the Depression. What is striking, though, is that this social work took place in an overtly patriotic framework. An institute visited by Coburn provided education for “girls from lower-class farm families”. They were trained in practical skills such as handicrafts, but also introduced to folk music and culture, and central to the whole exercise was discussion of German politics and the cultivation of a “national” culture. There was no belittling of non-German cultures, Coburn noted, but there was a notion of social development which saw it as an essential part of the creation of a better and stronger Germany. East Prussia, at the eastern edge of German territory, was a place where German identity was especially vulnerable. But the combination of patriotism and high principle is a thread that runs through other accounts of the period: for example, the portrait of Adam von Trott, executed in 1944 for his role in the Bomb Plot against Hitler (his name is on the memorial at Balliol), in the biography by Giles MacDonogh. This is not to say that Hitler wasn’t also motivated by nationalism, of course, just that German nationalism and National Socialism were not, despite Hitler’s best efforts, straightforwardly interchangeable. At any rate, what Coburn witnessed happening under the aegis of the Vaterländische Frauenverein, the Patriotic Women’s Association, suggests the environment in which Juscar spent his childhood. (I found the account of Coburn’s visit in C. Morgan, ‘A Happy Holiday’: English Canadians and Transatlantic Tourism, 1870-1930 (Toronto), 356-8.)

Juscar was born in 1914, and at the time of his father’s enforced retirement in 1933 was 18 years old, a student in Law with History and Economics at Munich University, having done a first term at Königsberg (it was standard practice to move between universities within one degree). In the same year he won the Rhodes Scholarship that brought him to Brasenose College, where he stayed for two years (earning himself a diploma in Economics and Political Science) from October 1933 to June 1935 before returning to Germany with the intention of finishing his law degree at Göttingen, where his parents now lived.

In actual fact he was obliged to serve with the army for the two years after his return to Germany, and only resumed his degree in October 1937. He remained a student until 1941, when he submitted a research dissertation. At Brasenose he was highly regarded, bright, engaged and (important for a Rhodes Scholar) a team player, rowing in the Brasenose 1st VIII. He and his contemporary Fritz Caspari, a determined opponent of the Nazi regime who left Germany in 1939, set up a scheme for non-German Rhodes Scholars to visit Germany. It was normal for German Rhodes Scholars to spend two rather than the standard three years at Oxford, but Ruperti left open the possibility of returning at a later stage for a third year. In the event, by the time he finished his law degree in Germany, war had broken out between the two countries, something the Rhodes Scholarship had been expressly designed to prevent.

In letters back to the Principal of Brasenose, William Stallybrass, excerpts of which were published in the college magazine at the time, Juscar describes military life, and offers his perspective on developments later in the 1930s. In 1936 he reads The Times of London while acting as an instructor of new recruits; in 1937, in a snowstorm in Lüneburg, he reminisces about rowing at Oxford; in 1938 he admits to a grudging fondness for military life, adding that the army “is one of the few institutions in this country, which are not so intensely affected by politics as most things are.” In June 1939 Stallybrass ends the “Principal’s Scrapbook” with a message from Juscar on “how genuine a wish for peace there was in Germany” (“This is a good note on which to end,” wrote the Principal). In 1941, under the heading “OUR GERMANS” he records that “J.C. von Ruperti (1933) has sent a message via America that he is well and at Göttingen writing a thesis.” At the time of his application for a Rhodes scholarship he was said to be aiming to join the Diplomatic Service. But he was soon back in the army, and in August 1943 was killed in Russia, in the aftermath of the decisive Battle of Kursk.

Photos of Juscar from his 1933 application to Brasenose

Back in 1938 Juscar had written to Stallybrass about the Anschluss of March 1938. It is the most challenging thing I’ve read related to Juscar, but it tells me again how well Hitler played the nationalistic consensus within Germany in the 1930s:

“As regards politics, I feel like sitting in a big bus, with perhaps a map, to ascertain from time to time where I am, but with not the least chance of influencing the course which the driver takes. I can’t say that I disagree with the driver’s choice of places where to get, and sometimes he even seems to take the right approach… Our bus, by the way, has been going at 100 m.p.h. again for some days in March; and again, as so often before, all the passengers were genuinely delighted to get where she took them. There was indeed general approval of the Anschluss and admiration for its speedy perfection, also among some parts of the intelligentsia as stand somewhat apart on many other occasions; since they, more perhaps than others, have a feeling for the historic importance of the development. Moreover, in this union of the Greater Reich a number of imponderables come into play, which is hard to explain, although their effects cannot be denied.

Please remember me to everyone in College. Oxford, I am sure, is as peaceful and pleasant as ever. May it continue like that for ever.”

Adam von Trott responded similarly to the Anschluss. MacDonogh comments that “it took a while before Trott was able to appreciate fully what had happened on 11 March, and to differentiate between a legitimate alteration of what he believed to be an unjust treaty [i.e. Versailles], and a step towards world domination on the part of a criminal adventurer” (p.114).

In the Brasenose archives, thanks to Georgie Edwards our archivist, I got to read the Vice-Principal’s Register (the minutes of the College Governing Body) and trace the process of approving and realising the plaque for Ruperti. When the process started, basic information was lacking. An initial proposal was made in June 1950, and approved by the college “if Mr Nicholas could find out whether [J.C. von Ruperti] was in fact killed during the war.” There is then silence for three years, by which time Juscar’s death, and date of death, had evidently been properly established. In September 1953 an approach was made to the renowned engraver Leslie Durbin, best known for a ceremonial sword presented to Stalin in 1943, but Durbin proved too expensive. The plaque, engraved in the event by Messrs William Pickford for £20, was finally affixed in 1954. On July 29, 1955 the Principal (by now Hugh Last) shared a message with the Governing Body from the Chairman of the Association of German Rhodes Scholars: “At their Annual Meeting held last month in Francfort, the association of German Rhodes Scholars, on being informed that a memorial to Justus v. Ruperti had been put up in the chapel of B.N.C., passed a vote of thanks for this chivalrous and noble act.” The German Rhodes scholarships were in fact suspended until 1969, as they had been after World War I until 1929. One of the first scholars after the suspension was lifted in 1969 was Juscar’s nephew, Lippold von Klencke.

There is a great deal that this record doesn’t say, especially about Barry Nicholas’ motivations for proposing this memorial, and the reactions of other members of the Governing Body. Perhaps there were none, but if so, why not? I can only assume that even in 1950 Nicholas had clear evidence that Ruperti was no Nazi sympathiser, and was, on the contrary, a man of liberal political opinions. Nicholas had also been a Brasenose student in the 1930s, and although he didn’t coincide with Ruperti, they must have had acquaintances in common. For me my confidence on this point came from a document that Juscar’s nephew Mr von Klencke was kind enough to show me, an entry from Juscar’s diary dated August 9, 1943, just a few days before his death.

It is a remarkable, and poignant, insight into his thinking. He describes the desperate situation he and his men found themselves in after the Soviet victory at Kursk, in headlong retreat, on the front line, and without air support. They were doomed, and knew it. In these circumstances Ruperti candidly shares with his diary his thoughts on Germany’s future, and then describes a friendly dispute about politics between himself and a fellow Oberleutnant from Hamburg, Grießbauer, the man who would communicate news of Juscar’s death to his family, and die himself soon after. There is patriotism in their conversation: they are both intensely concerned about what will happen to Germany. There is not a hint of Nazi ideology. Juscar writes of Germany’s need to find its way back from pride and arrogance to an awareness of human limitations, to value over and above the national interest the worth of humanity in general. “Germany must be strong and remain so, but internally just and just in its relations with neighbours and other countries, not guided by dogma but by concern for decency, human dignity, and mutual assistance.” “The value and freedom of the individual, though bound by Law and Justice, Morality and finally God, must be reestablished.”

I return again to that laconic phrase on the memorial, “Fighting for his country,” a simple (but heart-stopping) assertion of Juscar’s lack of ideology, his common humanity with the enemy that was commemorating him. In the first paragraph of the diary entry that patriotism, which I think is key to the story of Justus Carl von Ruperti (and which I think Barry Nicholas also thought was key), finds a different expression, as Ruperti talks about his responsibilities to his men (he was the commander of a “Schwadron” or company), and his attempts to give them the Germany they were very unlikely ever to see again:

“What depresses me most these days is that you cannot explain yourself to the men, cannot say to them how you really think… I ought to be totally frank with them even in these circumstances, but it can’t be done. It is too dangerous… All that’s left, then, is to try to understand them in human terms, to make this time easier for them, and to let them find a home (Heimat) in the comradeship of discipline and rules.”

In the words of Principal Stallybrass, this is a good note on which to end.

John Dryden to an unidentified person

A hardcore Latin-grammar blog, this one, leavened with some Jacobites. You have been warned.

Stephen Bernard, author of this excellent publication, is now producing an edition of the surviving letters of the poet John Dryden (1631-1700), and he’s asked me to help him make sense of what is known as Letter 7, a letter (now in the Beinecke Library at Yale University) written by Dryden to an unidentified correspondent. Latin grammar is my job, and Jacobites one of my longterm fascinations, and since one certainly and the other possibly feature in the story of this letter, I was hooked.

The subject of the letter is the celebrated translation of Lucretius’ masterpiece of philosophical poetry De Rerum Natura by Thomas Creech (1659-1700), first published in 1682, and specifically Creech’s version of lines 225-6 of the first book of the DRN. (At this point Lucretius is making his initial argument for atomism, that all matter consists fundamentally of tiny, indestructible particles.) It seems that someone had questioned whether Creech’s lines made any grammatical sense, and someone else had defended Creech; at which point Dryden was asked to adjudicate. In the letter he presents a series of arguments to the effect that Creech’s couplet could be nudged into making sense. Then, rather more convincingly, Dryden turns to the original text of Lucretius, translates it himself, and explains how Creech had misrepresented, if not positively misconstrued, the original Latin. For me the letter raises interesting questions about Dryden’s Latin, since his discussion of grammatical points seems more than a bit dubious. It’s always possible I’m failing to understand his point, though, and that should be borne in mind.

Here’s the letter in full:

“The two verses concerning which the dispute is raisd, are these;

Besides, if o’re whatever yeares prevaile

Shou’d wholly perish, & its matter faile,

The question ariseing from them is whether any true grammaticall construction, can be made of them? The objection is, that there is no nominative case appearing, to the word, Perish: or that can be understood to belong to it. I have considerd the verses, & find the Author of them to have notoriously bungled: that he has plac’d the words as confus’dly, as if he had studied to do so. This notwithstanding, the very words without adding or diminishing, in theire proper sence, (or at least what the author meanes[)], may run thus.– Besides, if whatever yeares prevaile over, shou’d wholly perish, & its matter faile,–

I pronounce therefore as impartially as I can upon the whole, that there is a Nominative case; and that figurative, so as Terence & Virgil amongst others use it. That is; The whole clause precedent is the nominative case to perish. My reason is this; & I thinke it obvious; let the question be asked, what it is that shoud wholly perish? or that perishes? The answer will be, that which yeares prevaile over. If you will not admit a clause to be in construction a nominative case; the word (thing) illud, or quodcunque, is to be understood; either of which words, in the femi[ni]ne gender, agree with (res) so that he meanes, whatever thing time prevailes over shou’d wholly perish & its matter faile.

Lucretius his Latine runs thus:

Praetereà, quae cunque vetustate amovet aetas,

Si penitus perimit, consumens materiem omnem,

Unde Animale genus, generatim in lumina vitae

Redducit Venus? &c.*

which ought to have been translated thus:

Besides, what ever time removes from view,

If he destroys the stock of matter too,

From whence can kindly propagation spring

Of every creature, & of every thing?

I translated it (whatever) purposely; to show that (thing) is to be understood; which as the words are here plac’d is so very perspicuous, that the Nominative case cannot be doubted.

The word, perish, usd by Mr Creech is a verb neuter; where Lucretius puts (perimit) which is active: a licence, which in translating a philosophicall Poet, ought not to be taken, for some reasons, which I have not room to give. But, to comfort the looser, I am apt to believe, that the cross-graind, confusd verse put him so much out of patience, that he wou’d not suspect it of any sense.

Sir,

The company having done me so great an honour, as to make me their judge, I desire from you the favour, of presenting my acknowledgments to them; & should be proud to heare from you, whether they rest satisfied in my opinion, who am, Sir Your Most Humble Servant

John Dryden.”

The problem that “the company” have identified with Creech’s lines is that there doesn’t appear to be any subject (the “Nominative case”, as Dryden describes it) for the verb “should perish”: it’s unclear what “shou’d wholly perish”, in other words. Dryden starts by acknowledging that Creech’s expression is poor, but then argues that if the words are less “confus’dly” organised (rearranged as “Besides, if whatever yeares prevaile over, should wholly perish, and its matter faile”), the construction makes sense and is also grammatical. In the next paragraph he expresses what seems to be the same point in more grammatical terms. The whole clause “Whatever years prevail over” is the subject of perish, he proposes, or else (an alternative version of the same idea) a word or phrase is unspoken but understood which stands for the previous clause and acts as the subject of the verb.

It’s actually quite hard to reconstruct Dryden’s thinking in this third paragraph, and part of the problem, I suspect, is that his mind is starting to wander from Creech’s translation to Lucretius’ original, which he goes on to quote and translate in the following paragraph. What makes me suspect this is that Dryden is making arguments he doesn’t need to make if his only aim is to rescue the grammatical status of Creech’s English (“whatever yeares prevaile over, should wholly perish, and its matter faile” makes perfect sense), but which he does need to make if he wants to establish that Creech’s English bears some relation to the grammar and meaning of Lucretius’ Latin. The fundamental problem there is that “whatever” in the Latin is quaecumque, which is a plural form (“whatever things”), and thus cannot be coordinated with the verb perimit, “perishes/should perish” (in Creech’s translation, but see below), because that is a singular form. Hence, I think, Dryden is tying himself into knots making “whatever years prevail over” a (singular) clause that is the subject of “should perish”, and then suggesting that, rather than treating the whole clause as a (singular) subject, one might understand a word/phrase like illud or illa res, “that thing”, recapitulating the preceding clause and acting as the subject of perimit. Quodcumque couldn’t work the same way as illud in such a construction anyhow, but Dryden seems to want to introduce quaecumque res, “whatever thing”, as if it might explain Lucretius’s quaecumque, or maybe Creech’s rendering of quaecumque. I’m struggling here, I admit, but I’m struggling because I can’t really make sense of Dryden’s grammatical argument, and I find myself wondering, heresy though it may be, that Dryden himself is struggling, too. None of the arguments he advances in this third paragraph can convince me that Dryden’s formal understanding of Latin grammar wasn’t, on this evidence, rather wobbly. There’s every chance I’m missing something, however, so please tell me if you think so.

In that paragraph Dryden may be heading for a γ=, but he’s on much safer ground in the next paragraph when he abandons Creech’s translation and offers his own. The major difference between his own translation and Creech’s is that, despite the fact that Creech was an Oxford academic, Dryden renders the Latin much more faithfully. As he explains in the penultimate paragraph, Creech took perimit to be an intransitive verb, a verb that has no object (this is what Dryden means by “neuter”, neither active or passive): “perish.” But perimit is in fact an active verb, “destroys”, and although Dryden politely treats Creech’s translation as a “licence” rather than an error, we may have our suspicions. In Dryden’s version (and I think this is the point of the prepenultimate paragraph, I translated it … cannot be doubted), the elusive subject of perimit is quite clear, if interestingly gendered: “he” in the second line is “time”. That, I think, is fine, but I’m still bothered by what seems to me a grammatical dog’s breakfast in the third paragraph.

Let’s just step back and wonder what occasioned the request to Dryden to adjudicate this dispute. Stephen Bernard thinks the letter may be to Anthony Stephens, an Oxford bookseller who published Creech’s translation of Lucretius, pointing out that Creech’s translation of this couplet changes between the first and third editions of this (phenomenally successful) publication in 1682: as if Stephens has consulted Dryden about Creech’s version, and then Creech had adapted his translation in response. Stephen knows everything about this period of English publishing history and is much more likely to be right (since I know absolutely nothing), but what makes me a bit sceptical is that although Creech’s translation changes, it doesn’t change in a way, I think, that someone who has read Dryden’s critique would change it. The new version is, “If all things over which long years prevail,/ Did wholly perish, and their matter fail,” which makes explicit the plural form in the Latin which may or may not have been bothering Dryden, but it continues to use the “neutral” verb “perish”, “a licence, which in translating a philosophicall Poet, ought not to be taken,” as Dryden had bluntly stated.

I’m not sure how strong a counter-argument that is, but another reason to wonder about a connection to Anthony Stephens is what for me is the most exciting thing about this letter, another letter that survived alongside it, dating to May 7, 1811, and written by Edmond Malone, apparently to the husband of a Mrs Smith who owned the Dryden letter as part of her “collection of autographs”: Malone had borrowed the letter, and in return supplemented Mrs Smith’s collection with one of Alexander Pope’s receipts for his “translation of Homer”, although he expresses regret that he couldn’t find any example of Shakespeare’s handwriting for her. (In this respect Malone and Mrs Smith were kindred spirits: Malone’s enthusiasm for autographs was such that he even cut out examples from historical manuscripts.) What Malone’s letter also does, however, is describe his conclusions about the addressee of Dryden’s letter.

From what he had heard from the Smiths about where the letter originated, Malone has been able to “ascertain, almost without a chance of error”, that Dryden had addressed his letter to Edward Radcliffe (though Malone calls him Francis), later the second Earl of Derwentwater, a person from whom Dryden might reasonably have hoped for support and patronage. Radcliffe was an interesting figure, a Catholic and a Jacobite; indeed one of his sons, James, was executed after the Jacobite rising of 1715, and another, Charles, after the 1745 Rebellion. Edward himself married an illegitimate daughter of James II, Mary Tudor, and all of this placed the Radcliffes very close to the royal family displaced by the Revolution of 1688: the letter is perhaps most likely to date to the family’s period of greatest influence during the reign of James II (1685-8), around which time Dryden also converted to Catholicism. The key evidence on which Malone bases this identification is the provenance of the letter. The seat of the Radcliffes was at Dilston Hall in Northumberland, and Malone informs us that it was at Dilston, “in a box containing papers of the Derwentwater family” (or possibly he means, in a box containing papers of the Derwentwater family from Dilston, but the difference is not significant), that the letter had been found.

(Edmond Malone, by his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds)

(Edmond Malone, by his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds)

Now Malone doesn’t help things by confusing Edward Radcliffe’s name with that of his father Francis, but if the detail about the box at Dilston is to be believed, it’s strong evidence of a connection with one of the Radcliffes, at least. What strengthens the case is the identity of our informant, Edmond Malone. I’m still only part way through Peter Martin’s biography of Malone, but the LRB review nicely summarises the achievements of this trailblazing literary biographer: “In the hands of this apparently diffident Irishman, the practice of literary history changed for ever: as far as the privileging of meticulous textual scholarship and painstaking archival research is concerned, Malone wrote the book.” Malone’s long hours in the archives ultimately ruined his eyesight, but he was instrumental in exposing the Chatterton forgeries, for example, and was the the first to establish a working chronology of the works of Shakespeare. Malone’s commitment to factual accuracy could even be felt to be excessive. Peter Martin describes his Life ofDryden, which introduced his edition of Dryden’s prose works (1800), as “the most thoroughly researched literary biography written up to that time” (p. 232), and he was satirised for a meticulousness of detail that tended to swamp his narrative. “The Life of A,” wrote George Hardinge in his parody The Essence ofMalone (1800), “should be the lives of B, C, D, &c. to the end of the alphabet.” But if it made for turgid reading, Malone’s determined recovery of the facts of Dryden’s (and Shakespeare’s) lives has ensured his status as a pioneer of scholarly method. If Malone says “with certainty” that the letter is addressed to Radcliffe, it’s a view worth considering.

Well, what I think this letter is about is a wager among upper-class men close to the Court. A dispute about a couple of lines from Creech’s famous translation arises, and it is proposed to resolve it by asking the Poet Laureate John Dryden to adjudicate: hence Dryden’s reference to a “looser” (of the wager) in the penultimate paragraph; and to his own impartiality in that difficult third paragraph; “company” in the final paragraph simply means the gathering of people present when the wager was struck and (presumably) the letter to Dryden was written.

That’s my theory, but let’s end by returning to the key question that this letter poses for a Classicist: was Dryden’s Latin a bit iffy? Since my whole being revolts at the thought, here is my final stab at an explanation, with thanks to Paul Davis for encouraging me to think less about the accuracy of what Dryden says in such private writing, and more about how he wanted to present himself. It’s a natural surmise that it was Radcliffe who believed that Creech’s couplet made sense and another member of the company (the loser referred to in the third person) who doubted it. Radcliffe was an important man, and Dryden had no wish to upset him, and hence the awkwardness of the letter, as Dryden tries everything he can to justify adjudicating that Creech’s inaccurate and internally nonsensical couplet does indeed make sense, as Radcliffe had wagered. From his familiarity with Dryden’s handwriting, Stephen could tell me that Dryden’s hand in this letter is unusually careful (such a wonderful observation to be able to make after the lapse of three hundred years!). Perhaps he is trying to impress the recipient of the letter; perhaps that is wild speculation. But it is surely true that “the looser” in this wager was robbed blind: Creech’s couplet was a stinker in all kinds of ways, but even on its own terms MAKES NO SENSE. Dryden’s adjudication was a travesty.

But maybe Dryden’s focus was less on grammar and more on forging or maintaining a potentially very fruitful relationship.

*My translation:

“Besides, whatever things time by lapse of years removes,

If it utterly destroys them, consuming all their material,

From whence is the race of animals, class by class,

restored by Venus to the light of life?”

Just a dog

A full-scale dog-blog was always on the cards. I came quite close in this one, when a figure in a photo I’d been shown turned out to be a pioneer of Afghan Hound breeding. But this blog is devoted to a single dog, a fox terrier called Dash who belonged to the archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein.

A full-scale dog-blog was always on the cards. I came quite close in this one, when a figure in a photo I’d been shown turned out to be a pioneer of Afghan Hound breeding. But this blog is devoted to a single dog, a fox terrier called Dash who belonged to the archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein.

Actually Stein owned seven dogs in succession, and every one of them was called Dash. The name was more common at one time than it seems to be now: Queen Victoria’s Dash was a King Charles spaniel. It still seems slightly odd to give every one of a sequence of dogs the very same name, and Stein, whose claim to fame is above all as an investigator of the Buddhist cultures of Central Asia, sometimes toyed with the idea that the latest Dash was a reincarnation of one of its predecessors.

Anyhow, the subject of this blog is Dash II, or “Dash the Great” as Stein liked to refer to his very favourite of them all; he also called him Kardash Beg, “The Honourable Snow Companion”, when he discovered with delight that his new dog had a relish for snow. Pets belonging to Aurel Stein could expect to encounter some pretty gruelling climatic conditions.

Stein acquired Dash the Great in 1904, and the dog accompanied him on his Second Expedition into Central Asia from 1906 to 1908, Stein’s most audacious, most successful, and ultimately most controversial venture into Chinese Turkestan. It was during this expedition that Stein was able to investigate a trove of Buddhist material in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang, removing a large quantity of texts, textiles and paintings. But earlier in the expedition he and his team had made the high-altitude crossing from the very northeastern tip of Afghanistan into Chinese Central Asia, and later he undertook a perilous, and very nearly disastrous, crossing of the Taklamakan desert.

Dash is a regular presence in Stein’s accounts of his expedition, especially the popular Ruins of Desert Cathay (1912), often most visible in moments of particular intensity. As things become very desperate during Stein’s crossing of the Taklamakan desert, his men threatening to mutiny, he is grateful that Dash makes do on “a saucerful [of water] spared from my cup of tea”. As they scale the 16,000-foot Wakhjir pass between Afghanistan and China, the generally irrepressible terrier whimpers with the cold and insists on sheltering beneath Stein’s fur coat. On another occasion he’s roused from sleep in Stein’s tent by the excitement of Stein and Chiang-Ssu-yeh, Stein’s “Chinese secretary and helpmate”, when they find proof that the frontier fortifications they’re investigating date from as early as the first century AD.

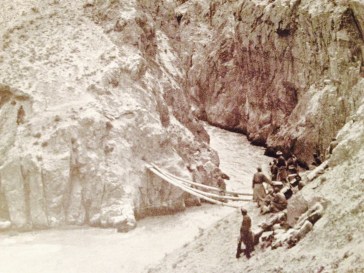

Dash chases marmots in the high country, “distinctly provoking for so indefatigable a hunter”, develops a knack of mounting a horse, “jumping up to the stirrup, and thence to the pommel of whoever was offering him a lift”, and gets badly mauled by a pack of semi-feral sheepdogs. When the party finds itself having to cross the Kash river over a ridiculously makeshift bridge, the poor thing is trussed up in a bag and passed along a wire rope along with the rest of the baggage.

The expedition took its toll on Stein. As he crossed back into India in 1908 he suffered frostbite while surveying at high altitude, losing several toes of his right foot after being carried down in agony to Ladakh. When he was eventually fit enough to travel, he describes his departure for Britain at the end of 1908 and enforced separation from Dash, “the last of my faithful travel companions, but, perhaps, the nearest to my heart”: dogs were not allowed on the P. & O. Mail boat. Dash made his own way to Britain on a separate steamer, spent four months in quarantine, and “was joyfully restored to his master under Mr P. S. Allen’s hospitable roof at Oxford.”

P. S. Allen was a Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, and he and his wife Helen were scholars of Erasmus and two of Stein’s oldest and closest friends; their “hospitable roof” was 23 Merton St., where Stein always stayed on his visits to Britain, and where Dash would actually spend the rest of his life. Stein seems to have decided that his “inseparable little companion” had had enough adventure. At any rate, when he returned to India he left Dash behind with the Allens. The comfortable new home of this canine veteran of the sand and snow deserts of the Taklamakan and Pamir Knot is now part of the Eastgate Hotel.

Dash lived with the Allens for another nine years, and while Merton St. was his home, he was clearly left to wander wherever he liked across Oxford. But as the First World War drew to a close, a new and deadly threat to an increasingly decrepit old dog was being introduced to Oxford’s streets, the motorised Omnibus. Percy Allen wrote to Stein to explain what happened:

He took himself out for a walk one aft. Friday, 27 Sept. [1918], & was run over by a motor bus in Park End St—the street which goes down to the station as the continuation of the High & Queen St. The police brought around his collar next morning, & reported that he had been killed instantaneously, & that they had buried him in their usual place. Helen went to the police station to enquire, as soon as we returned home—10 days later—but by that time it was too late to unearth him & bring him to sleep in the garden where he has so often slept before.

It’s a terribly banal end for a dog who’d seen so much, run over by a bus on Park End St. (Although I’ve subsequently walked the distance from 23 Merton St to Park End St, and Dash clearly hadn’t lost his wanderlust.) Soon the regular letters between Stein and the Allens turned back to the urgent issues of the day, the Armistice just a month or so after Dash’s death, and the Spanish Flu. But for as long as Dash is the focus of these letters between old friends, he provokes a touching outpouring of affection between them. Helen Allen reminisced to Stein about Dash’s life in Oxford:

He has been as outstanding amongst dogs, as his master amongst men; such sagacity & such devotion. I can see him in so many different poses: returning on a Cotswold walk after a chase after a hare, to look which way we were gone meanwhile, locating us & then heading straight for our slow plodding figures; looking up full of enquiry when he heard: “Go and meet him, Dash,” & then bounding forward joyously as he caught sight of Percy…

Such faithfulness as he has shown must surely meet a fit reward.

And we send you many thanks for the added happiness you brought into our lives through Dash.

“Surely a Ulysses among dogs,” wrote Percy Allen to Stein:

full of wise counsel & dignity, & greatly attached to his friends. You brought great pleasure into our lives thro’ him: for wh. we thank you, amice noster, as for so much else. Blessings on Dash the Great.

Stein, in response, thanked his friends for their comforting words: